Hammitt Journal

Step into Spring: New Arrivals are Here!

Punxsutawney Phil may have declared six more weeks of winter, but spring has officially sprung here at Hammitt, and our newest drops are something you won’t want to miss.

Step into Spring: New Arrivals are Here!

Punxsutawney Phil may have declared six more weeks of winter, but spring has officially sprung here at Hammitt, and our newest drops are something you won’t want to miss.

New Year, New Debuts

You know what they say, “New Year, New Me”, but here at Hammitt, we prefer “New Year, New Bags.” An array of new Hammitt bags just hit the market, just...

New Year, New Debuts

You know what they say, “New Year, New Me”, but here at Hammitt, we prefer “New Year, New Bags.” An array of new Hammitt bags just hit the market, just...

The Best of Hammitt 2025: A Year in Review

Let’s recap our best launches of the year!

The Best of Hammitt 2025: A Year in Review

Let’s recap our best launches of the year!

‘Tis the Season

It’s the most wonderful time of the year!

‘Tis the Season

It’s the most wonderful time of the year!

Champion Breast Cancer Awareness this October w...

October is Breast Cancer Awareness Month, a month dedicated to educating, detecting breast cancer early, and supporting survivors and those living with metastatic breast cancer. All month long here at...

Champion Breast Cancer Awareness this October w...

October is Breast Cancer Awareness Month, a month dedicated to educating, detecting breast cancer early, and supporting survivors and those living with metastatic breast cancer. All month long here at...

A Look Back at Hammitt's Hawaiian Holiday 2024

There’s no better feeling than unboxing a new brand Hammitt, right? But it gets even better when it comes at a discounted price. Each November, we host our one and...

A Look Back at Hammitt's Hawaiian Holiday 2024

There’s no better feeling than unboxing a new brand Hammitt, right? But it gets even better when it comes at a discounted price. Each November, we host our one and...

ITT GIRLS

This just in: all the cool girls are wearing Hammitt (you should too). From the red carpet to the Rosewood Miramar, Hammitt bags are carried by ITT girls everywhere you...

ITT GIRLS

This just in: all the cool girls are wearing Hammitt (you should too). From the red carpet to the Rosewood Miramar, Hammitt bags are carried by ITT girls everywhere you...

Our 2025 September Edition: Belted Suede

From runways to everyday, belts are making a big comeback this Fall in fresh, bold ways.

Our 2025 September Edition: Belted Suede

From runways to everyday, belts are making a big comeback this Fall in fresh, bold ways.

Elevated Essentials for Him from the Hammitt Me...

At Hammitt, we are more than just a premium leather handbag brand - but you already knew that. You may not know that we have an entire collection of elevated...

Elevated Essentials for Him from the Hammitt Me...

At Hammitt, we are more than just a premium leather handbag brand - but you already knew that. You may not know that we have an entire collection of elevated...

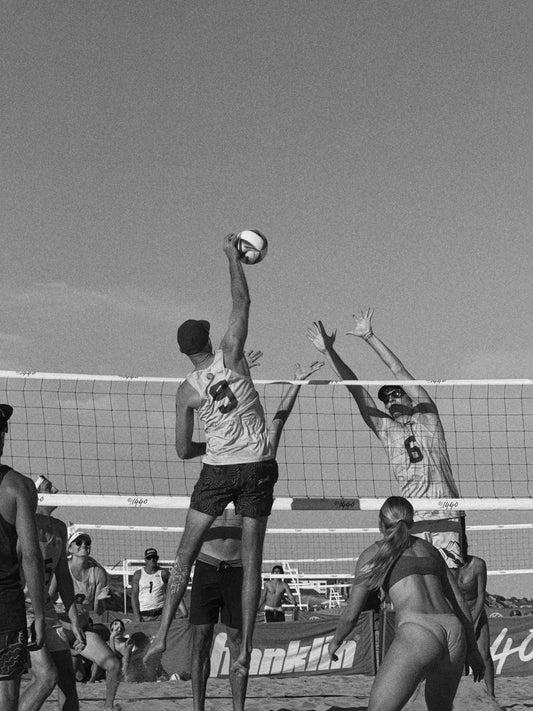

A Coastal Classic: Recapping the AVP Manhattan ...

Over the weekend, HAMMITT headed to the AVP Manhattan Beach Open for some fun in the sun and, of course, beach volleyball.

A Coastal Classic: Recapping the AVP Manhattan ...

Over the weekend, HAMMITT headed to the AVP Manhattan Beach Open for some fun in the sun and, of course, beach volleyball.

A-List Essentials

From the red carpet to coffee runs, these HAMMITT handbags are making headlines.

A-List Essentials

From the red carpet to coffee runs, these HAMMITT handbags are making headlines.

Jenna Ortega Celebrates the Release of 'Wednesd...

Have you ever stopped to ask yourself: WWWW? (What Would Wednesday Wear?) We know just what Wednesday actress Jenna Ortega would wear - a brand new Hammitt! Earlier this month,...

Jenna Ortega Celebrates the Release of 'Wednesd...

Have you ever stopped to ask yourself: WWWW? (What Would Wednesday Wear?) We know just what Wednesday actress Jenna Ortega would wear - a brand new Hammitt! Earlier this month,...

Hammitt in the Hamptons

Hampton Volley called, and we answered! Last week, our marketing team took off to the Hamptons for a week filled with summer fun, meaningful connections, and of course, beach volleyball....

Hammitt in the Hamptons

Hampton Volley called, and we answered! Last week, our marketing team took off to the Hamptons for a week filled with summer fun, meaningful connections, and of course, beach volleyball....

Red Carpet Energy

Spotted, Julie Bowen, and an oh so elegant Hammitt evening bag, turning heads on the red carpet of Netflix’s Happy Gilmore 2 premiere earlier this week. Everyone is talking about the movie...

Red Carpet Energy

Spotted, Julie Bowen, and an oh so elegant Hammitt evening bag, turning heads on the red carpet of Netflix’s Happy Gilmore 2 premiere earlier this week. Everyone is talking about the movie...

Your Favorite Shoulder Bag Just Got Bigger and ...

Introducing the Kyle Med, the newest edition to our Kyle family. The Kyle Med has the same easy to use features as our bestseller - now offered in a larger...

Your Favorite Shoulder Bag Just Got Bigger and ...

Introducing the Kyle Med, the newest edition to our Kyle family. The Kyle Med has the same easy to use features as our bestseller - now offered in a larger...

Let Them Eat Cake

It's our Manhattan Beach store's 4th birthday!

Let Them Eat Cake

It's our Manhattan Beach store's 4th birthday!

The Summer 2025 “It” Accessory: Bag Charms

Bag charms are back and better than ever. The recent bag charm hype began in 2024 and hasn’t lost momentum yet. In fact, it seems to be gaining even more...

The Summer 2025 “It” Accessory: Bag Charms

Bag charms are back and better than ever. The recent bag charm hype began in 2024 and hasn’t lost momentum yet. In fact, it seems to be gaining even more...

The Ultimate Guide to Finding the Perfect Clutc...

Looking for an elevated take on a basic handbag? Clutches effortlessly blend style and functionality, complementing any outfit. A high-quality clutch helps you look your very best, while keeping your...

The Ultimate Guide to Finding the Perfect Clutc...

Looking for an elevated take on a basic handbag? Clutches effortlessly blend style and functionality, complementing any outfit. A high-quality clutch helps you look your very best, while keeping your...

Clear the Way: Must-have Clear Bags for Concert...

Summertime is here, and you know what that means - festival season and summer gamedays are underway! Warm nights call for outdoor concerts and baseball games, it is essential that...

Clear the Way: Must-have Clear Bags for Concert...

Summertime is here, and you know what that means - festival season and summer gamedays are underway! Warm nights call for outdoor concerts and baseball games, it is essential that...

Summer 2025 Travel Edit: The Charles Crossbody

Meet your perfect summer travel companion: the Charles Crossbody. Whether you are embarking on a European summer, tropical getaway, weekend roadtrip, or maybe even a staycation, the Charles Crossbody will...

Summer 2025 Travel Edit: The Charles Crossbody

Meet your perfect summer travel companion: the Charles Crossbody. Whether you are embarking on a European summer, tropical getaway, weekend roadtrip, or maybe even a staycation, the Charles Crossbody will...

Call The Doctor; We have a Case of the Weekend ...

There’s nothing a brand new Hammitt can’t cure! We are excited to launch weekend blues; your go to tran-seasonal collection to round out the HOTTEST summer ever and offer a...

Call The Doctor; We have a Case of the Weekend ...

There’s nothing a brand new Hammitt can’t cure! We are excited to launch weekend blues; your go to tran-seasonal collection to round out the HOTTEST summer ever and offer a...

I’ll take one Manhattan please - on the rocks!

Hammitt here, your one and only source of all things trending and oh so stylish. Every September we release a limited edition + show stopping collection inspired by our most...

I’ll take one Manhattan please - on the rocks!

Hammitt here, your one and only source of all things trending and oh so stylish. Every September we release a limited edition + show stopping collection inspired by our most...

Don’t Mess with Texas...Tapestry, Y'all

Feeling nostalgic? Top Gun has returned, Jen and Ben have reunited and an all time favorite Hammitt print is making a comeback! Introducing Texas Tapestry; an homage to our beloved...

Don’t Mess with Texas...Tapestry, Y'all

Feeling nostalgic? Top Gun has returned, Jen and Ben have reunited and an all time favorite Hammitt print is making a comeback! Introducing Texas Tapestry; an homage to our beloved...

Meet Our Designer's Favorite...

The fall season has officially started, and with it the arrival of our gorgeous new mahogany suede collection! The secret is out: this rich cognac suede is a favorite of...

Meet Our Designer's Favorite...

The fall season has officially started, and with it the arrival of our gorgeous new mahogany suede collection! The secret is out: this rich cognac suede is a favorite of...